The post Behind Every Brave Horse Kid Is A Brave Horse Parent appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>I’ve recently watched helplessly as two of my daughters fell off their horses. It had been a while since I’d seen one of my daughters tumble, so I’d forgotten that instinctive panic—that intense urge to leap into the ring, wrap her in my arms, and whisk her off for ice cream, safe from harm. I’d forgotten how uncomfortable it feels to sit with the fear, keep my emotions in check, and let my kid work through it.

But what I didn’t forget is why we say, “Get back on the horse.” Getting back on after a fall is a profound life lesson for kids: When things feel hard and scary, we push through rather than throw in the towel. And though riding comes with risk, risk comes with reward: a lifetime filled with passion, grit and resilience.

Still, when I watched my teen fall last month, I had to stop myself from spiraling. She had barely settled into the saddle when a loud bang shook the indoor. Understandably, the horse jumped sideways, and off she went. Slam! Down hard on her back. We were alone in the arena and hadn’t realized the farm owner was fixing a broken door.

“Are you OK?” I yelled. But she was already on her feet, dusting off her purple breeches.

“Is there dirt on my shirt?” she asked. “A little,” I said, brushing at it as she headed back to the mounting block.

I inhaled deeply and stayed quiet. She could do this.

When her trainer arrived, she could tell my daughter was rattled, especially as the horse approached the noisy door.

“Let’s put him to work,” she said gently.

My daughter mustered the courage to trot at the far end of the ring, still avoiding the door. Her trainer gave her grace: “We have all the time in the world,” she reassured when my daughter apologized for her nerves.

As the lesson progressed, they warmed up over small jumps.

“I know you’re looking out the door because you’re on edge, but he’s fine,” her trainer told her. “Push him forward.”

By the end of the lesson, my kid was herself again, riding fluidly and confidently, ignoring the monster door. She did it!

Next time, I thought to myself, she’ll remember to shorten her reins immediately and get right to work. She’ll know she can handle what comes her way.

Even so, getting back on takes real guts—hers, of course, but mine too.

It’s rough watching your child take a hard fall and then watching them get on again. It takes guts to keep encouraging them to do a sport that is riskier than something with a net (or, let’s face it, riskier than nearly any other hobby). It’s brave to say, “You got this,” when your own anxiety is flipping around in your stomach. But you put on your game face, cheer for your kid, and video her rounds for her.

At a show several weeks later, I think I passed the brave-mom fall test again. Though honestly, I’m still mulling it over. My 8-year-old was thrilled to move up to short stirrup: her first real courses; her first flat classes with a canter! Yippee! And these were proper courses—singles, diagonals, not just outside lines. She wasn’t intimidated; she was excited to do the “big kid stuff” like her sister.

Her first classes, just walk-trot, went smoothly. Then came her first real cantering class. Things were perfect until, out of nowhere, her saintly schoolmaster kicked out. Though she tried her darndest to stay on, he unseated her and she slid to the ground. When she popped up, a broken jack-in-the-box, dusty tears were staining her face.

They stopped the class, and she ran right into my open arms.

“I’m scared to get back on,” she whispered, her tears soaking my shirt. “And I’m embarrassed.”

“I get it,” I told her. “You can do whatever you’re comfortable with. No pressure if you don’t want to canter today. But it is important to get back on.”

Still sniffling, she mounted up. She finished four more classes. Though she trotted her fences rather than cantering, the crowd cheered mightily for her.

Strangers came up to her afterward with encouragement: “You almost stuck that! You’re brave!” She smiled a little brighter. “That wasn’t your fault! It came out of nowhere,” the EMT told her as we headed to the trailer to untack. I watched her posture change. She walked taller, confidence restored, soaking up the reassuring words—and basking in her own courage. She had confronted her worst fear and won.

And I knew that next time, she’ll press into her heels a little harder, sit up a little taller, be ready to face the unexpected.

After the show, we debriefed over Frappuccinos.

“I know things didn’t go exactly how you planned, but it was still a great day,” I said. She agreed. “It was an amazing day. But why did he do that?”

“We won’t ever really know,” I admitted. “Could’ve been the photographer crouched in the grass. Could’ve been a nasty horsefly bite. Could’ve been an off day.” She waited for more. But I didn’t have more.

“Horses are horses. They’re not always predictable. And this stuff is going to happen again. It’s part of being a horse girl. You fall off. You get back on. It makes you stronger.” Then I pulled her close. “I’m proud of you.”

Luckily, that was enough for her.

As a mom, my instinct is to protect. To keep my kids safe. To rush in. To stop them from ever getting hurt.

But I keep learning to fight those instincts. Because by stepping back, letting them face the falls and the fears, I’m raising brave girls. Girls who don’t shrink from risk or failure, who know that bravery isn’t the absence of fear. It’s deciding to keep getting on the horse despite it.

And you know what else I’ve realized?

It isn’t just our horse kids who carry that kind of grit in their hearts. It’s us, too. The parents in muddy sneakers and sweat-stained baseball hats, clutching our cameras, standing at the rail with pitter-pattering hearts, cheering with smiles that mask our fears.

Parents who wake up in the dark to braid ponytails and secure bows. Who sacrifice our own dreams to write checks for lessons. All the while, quietly hoping each time for another safe ride.

All of us who fight the urge to wrap our kids in bubble wrap, and instead whisper, “You’ve got this.” Or as I like to say to my kids, “You’re a beast.”

It takes a special kind of courage to let your kids fall. And an even greater kind of love to encourage them to get back on.

Jamie Sindell has an MFA in creative writing from the University of Arizona and has ridden and owned hunters on and off throughout her life. She is a mom of five kids, ages 4 to 15. She and her family reside at Wish List Farm, where her horse-crazy girls play with their pony and her son and husband play with the tractor.

The post Behind Every Brave Horse Kid Is A Brave Horse Parent appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Horse Vs. Calendar: How Do I Keep It Together When The Plan Falls Apart? appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Have a question for Stable Sage? Email it to coth.advice@gmail.com. We reserve the right to edit your submission for clarity and length, and we promise to keep it anonymous.

Dear Stable Sage,

I’m an eventer, and I love a good plan. I’ve got a training spreadsheet that takes me from now until THE BIG EVENT, with every trot set, jump school and dressage ride mapped out in color-coded glory. The problem: My horse doesn’t care about my calendar. Last week we lost a shoe, this week our gallop and jump lesson got rained out, and the whole plan feels like it’s unraveling. I’m panicking that if I fall off schedule, we won’t be ready. How do I balance sticking to the plan with listening to my horse?

Type A With a Stopwatch

Dear Type A,

Your spreadsheet sounds beautiful. But here’s the inconvenient truth: Your horse did not get the link to that Google Sheet.

Horses don’t run on our timelines; they run on horse time. And horse time includes things like “mystery body soreness” and “let’s play another round of ‘either my leg is broken or I’ve got an abscess.’ ” None of this was in your carefully crafted plan, and yet here we are.

Now, don’t toss the spreadsheet in despair. It’s a useful tool. But think of it as a compass, not a contract. It points you in the right direction, but you’ve got to be flexible enough to take detours when the horse says, “Nope, not today.”

A wise man named André 3000 once sang, “You can plan a pretty picnic but you can’t predict the weather.” Horses are famous for taking our best laid plans and pooping all over them. In a way, the unpredictable is actually predictable. You don’t know the details, but you do know there will be curveballs.

So when you build out your calendar, build in a cushion. Some horses are more drama-prone, others are stoic, and their previous track record can suggest how thin or plush that cushion needs to be. Either way, lost time is part of the sport. You can always use an extra walk hack day if you’re ahead of schedule, but you can’t conjure up extra days if you planned yourself into a corner.

And let’s not forget that you, the rider, are 50% of the equation. Pushing through has become a weird, messed-up badge of honor in horse culture, but it should be OK for you to take a beat when you need it. Even if it’s 72 degrees, the footing is perfect, and “cross-country school” is screaming at you from your spreadsheet in highlighter yellow—if you’re sick, exhausted or just not in the headspace to gallop your horse at solid obstacles, the smarter (and safer) choice is to call an audible.

Horses will make you crazy if you don’t approach all this stuff with a little zen. Don’t let The Big Event become your whole personality or consume your whole bank account. Because if it doesn’t happen—and there’s always a chance it won’t—you’ll need something sturdier than a nonexistent refund policy to fall back on.

Progress with horses isn’t linear. It’s a scribble: good days, vet days, rain days and “my horse just pulled his shoe off in the trailer and apparently threw it out the window” days. The spreadsheet gives you structure, but at the end of the day your horse is the one that has to sign off on it.

Your horse doesn’t know what day The Big Event is. He only know how you show up for him today. And showing up with flexibility, patience and a willingness to crumple the plan when needed is what keeps you both sound, in body and partnership.

So keep your spreadsheet. Just make sure you’ve got an eraser handy.

The post Horse Vs. Calendar: How Do I Keep It Together When The Plan Falls Apart? appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Unmounted Make-Up Lessons Work For Students And Instructors Alike appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Three years ago, our riding program switched to a semester-based format, and we haven’t looked back. The switch has resulted in greater financial security for the barn and instructors and a greater sense of commitment from our riders and families. We’ve changed very little of the new format since we put it into place in January 2022.

But we have struggled figuring out how to handle missed lessons. We wanted a make-up policy that was fair to our families, but that didn’t add extra stress or unpaid work time for our instructors.

What Wasn’t Working

Prior to the switch to a sessions format, we—like many programs—had a 24-hour cancellation policy. If a client cancelled a lesson more than 24 hours in advance, it was eligible for a make-up, which the instructor had to fit into her schedule, either during another cancellation or before or after her regular lessons. These make-ups were time-consuming to both schedule and teach, and if that empty lesson spot couldn’t be filled, then instructors were tied up for the duration of two lesson spots but only being paid for one.

And when lessons were cancelled inside that 24-hour window, we often had to chase down payments for those missed lessons. It was time-consuming and uncomfortable; despite the policies being in writing, we often felt like the bad guys.

When we switched to a semester- or sessions-based format, we went back and forth as to how—or whether—to offer make-ups.

Our sessions are generally 10-12 weeks long, and we felt that one make-up lesson during that session (and two during the summer session to account for vacations) was fair. Three years later, we still feel this way, and I can’t remember an instance where parents have pushed back against this.

When we first went to a session format, we’d select a few days after the end of each session to offer make-ups, and we’d post a sign-up sheet with open lesson slots. But allowing people to sign up on their own didn’t enable us to balance beginner, intermediate and advanced lessons on a single day. If more beginners, for example, signed up on one day, then those beginner-specific horses carried a heavier load.

It also meant that the days were often very broken up—maybe one person signed up for a 10 a.m. lesson, then the next make-up wasn’t scheduled until 2 p.m. For instructors who live on property it may not be a big deal (I can run home and switch a load of laundry), but it’s a lot of wasted time for those who travel. And finally, if you’re teaching three days of make-up lessons, those are essentially unpaid work days added on to the end of the session. We ran make-ups like that for about a year, then decided there had to be a better way.

Enter The Unmounted Make-Up Lesson

Our program emphasizes horsemanship, and our students know that to progress up our levels, there are both mounted and unmounted skills that they have to learn.

We kept that in mind as we brainstormed make-up lesson options, and came up with this: unmounted, two-hour group lessons where students can practice the horsemanship skills that our program values.

We announced the change in one of our pre-session calendar/newsletters, and no one batted an eye. Toward the end of the session, we posted a sign-up sheet for three make-up slots offered over several days. If this worked, instead of taking upwards of 30 hours to offer each student a make-up ride, in just six hours we could offer everyone additional time at the barn to take the place of a missed lesson.

Every student loves extra time at the barn, so the two-hour chunk of time is something they all look forward to. And because many of our regular lessons are privates or groups of two, the make-up sessions give our students a chance to hang out with a bunch of like-minded, horse-crazy kids—another plus.

This new format has been a huge hit. Every student loves extra time at the barn, so the two-hour chunk of time is something they all look forward to. And because many of our regular lessons are privates or groups of two, the make-up sessions give our students a chance to hang out with a bunch of like-minded, horse-crazy kids—another plus.

The level(s) of the students in each make-up group helps determine the skills we’ll practice during that time. At the last make-up session I taught, each rider picked a skill from their current level that they wanted to practice, and then the rider(s) at the next level up taught that skill to the lower-level rider. Watching my more advanced students teach something to our newer riders made me so proud!

We’ve been offering make-ups in this way all year, and they’ve become days in the calendar year that our riding students—and our instructors—look forward to for camaraderie, education and fun.

Sarah K. Susa is the owner of Black Dog Stables just north of Pittsburgh, where she resides with her husband and young son. She has a B.A. in English and Creative Writing from Allegheny College and an M.Ed. from The University of Pennsylvania. She teaches high school English full-time, teaches riding lessons and facilitates educational programs at Black Dog Stables, and has no idea what you mean by the concept of free time.

The post Unmounted Make-Up Lessons Work For Students And Instructors Alike appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post A Week In The Life: The US Dressage Festival Of Champions appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Friday, Aug. 15

It’s 3 a.m., and I’m up and at ’em. We’re on night turnout most of the year, so I fetch Cadeau from his field. A notoriously slow and finicky eater, I give him an hour to finish his breakfast. But he’s already suspicious—being able to read a clock and all—and then I commit my first crime (of, I’m sure, many) of the week: I give him a dose of a gastric support paste. After spending half an hour acting like I’ve tried to poison him, he barely nibbles at his breakfast and then gives up to stare out the window at the trailer.

This will be a long day.

Cadeau went through a period of not getting on the trailer, and I spent a lot of time working on it with him, so I’m delighted when he waltzes right on. But that’s the last easy piece of the day. The trip from our base in Virginia to Lamplight Equestrian Center in Wayne, Illinois, should take 12.5 hours. Instead, it takes almost 14 because of traffic in Indiana and around Chicago.

While Cadeau does graciously drink about half a bucket of water, he doesn’t touch a bite of hay the entire way. Big lesson of the weekend: I’ll need to experiment with different types of forage when he travels a long way. And I also wonder if maybe he is upset because he’s traveling alone. Further study is needed.

I unload, settle him in (he dives right for the hay in his stall, thank goodness), then go to unhook the trailer and drop my stuff at the hotel before coming back to do night check. He hasn’t touched his water. The next morning, only about half a bucket is gone. His gums and skin are good, and he does settle in and eat some grass when taken out for a graze, but I don’t like it.

By the way, it is now…

Saturday

My plan was to just hack today, so I pop on him before it gets too hot, and he’s perfectly polite but pretty crunchy from the trip. I don’t want to burn any more calories or hydration than necessary, but I do break protocol a bit and do a few minutes of glacial, boring, head-on-the-floor trot. After a few minutes of this, his back lets go, and he takes a big deep breath. This was the right call.

I spend the rest of the day tidying the tack stall I’ll be sharing with the daughter of one of my syndicate members, who will be arriving later to do the Dressage Seat Medal and the Children’s division, getting a workout in, and taking a nap—a luxury I rarely get.

Cadeau is eating normally, phew, but still not really drinking. I try electrolytes in the water, no dice. I throw an apple into his bucket, and he slurps down about half trying to get the snack, but when he can’t get his teeth into it, he gets mad and gives up. All his hydration indicators are still OK, though, so I head to bed with my fingers crossed.

Sunday

Same story: He’s had a little water but not enough. Now this is serious. Someone gives me a handful of chopped alfalfa, and that he likes, so I find a local supplier, and give him a bucket of that in water. He just about knocks me down to get to it. Another big lesson of the weekend: Be prepared for Cadeau to not drink when we travel somewhere new.

My plan for the day had been to just fluff around, do some transitions, get Cadeau loose, make sure my half-halt works, and be done. It’s a long week, and while Cadeau is plenty hot, he is not limitless in his muscular capacity.

I also had planned on doing this without a coach. But last night, I started getting the yips, mostly because I’d seen so many riders really schooling the day before, and not just doing what I did, toodling about. I am an experienced competitor and not a nervous one, but I feel myself getting into my head.

I do most of my riding with Ali Brock, but Olivia LaGoy-Weltz (who is both a deeply trusted friend and my neighbor of sorts, only 45 minutes from me in Virginia and around the corner in Florida) has just been named to the USEF coaching staff, which means she’s at the show in person. I’d taken a few lessons with her over the last few weeks at home in Virginia, so we’d have some mileage together and some common language before the show.

So, Olivia to the rescue. She just sits with me and chats, occasionally chiming in about what I’m doing, but mostly just keeps me company, and keeps me confident in my plan. She texts me an hour later: “I’ve been sitting at the ring watching a whole lot of people who seem to have forgotten the show starts tomorrow. Your ride was so soft and nice to watch.” Sometimes your coach is your coach; sometimes your coach is your emotional support animal.

Speaking of animals, my staff at home text me a picture of one of my dogs, face swollen and covered in blood. (Fact: one of my animals gets hurt every time I am gone for more than a handful of days. This one sees the vet, gets a diagnosis of an infected tooth, and goes home with meds. She’ll be fine.)

Bath, braid and put on my jog outfit: a super cute, thrifted button-down shirt, jeans, brand new sneakers that immediately rub a hole in my foot. Cadeau is perfectly polite to jog, with the caveat of stopping mid-trot to do a full body shake like the Thellwell Pony/Serious International Horse he is. Passed.

There’s a rider briefing with the stewards—don’t ride like a jerk, don’t be a twit on the internet, don’t blast on your noseband, the usual—followed by a wine and snack party. I love the big championship shows for so many reasons, but one of them is that I get to see my old friends from all over the country and make some new ones. I’ve had a girl crush on Sarah Mason-Beaty and Laura DeCesari—both badass trainers making their own Grand Prix horses—for a while, so it’s cool to put faces to names. I’d love to sit around and drink and socialize but one of age 40’s gifts to me is a complete inability to sleep through the night if I have a glass of wine, so it’s night check (Cadeau, mercifully, HAS been drinking, whew), and then off to bed, until it’s…

Monday

I’ve been so fortunate as to draw a time towards the end of the class; we can talk about it all day long, but statistics are in favor of those towards the end. But it also means that I get to sweat for a while, because this class is big, and this class is GOOD—like, really good. I came in ranked No. 10 in the country on a 69% average. And this show, for me, is not about the ribbons; it’s about learning how to show Cadeau well under conditions I can’t replicate any other way, ones where he’s gone for a week, to somewhere totally new, having to be in top shape for three days of showing. This is a fact-finding mission.

But who am I kidding? I also like ribbons a lot. Especially primary-colored ones. So I’ve done my homework, and my horse feels amazing. Let’s go.

I warm up, and I’m sticking to the plan: Give him time to get loose, transitions, long arms, forward-thinking contact. A few walk breaks; he likes them, rather than just building and building. Touch a pirouette each way, touch a zig zag, touch some changes. Walk pirouettes. And finish with a calibration of the trot, because Cadeau has amazing adjustability in the trot, but I’m not yet in charge of it, so I need to pick the one that feels the most consistent, and stay there. In my head, the “good” one is always so much slower than I think it should be, so I need a grown up to tell me to stick to it.

And then it’s go-time. I know I shouldn’t get ahead of myself, and I know it’s a long six minutes, but I can’t wipe the smile off my face as I go around the ring, because Cadeau is ON. He feels like a soda bottle I’ve shaken, and I can just sit back and slowly release the bubbles.

There are the little things, of course. One walk pirouette gets weird. The right canter half-pirouette, my pride and joy, is so nice that we have a miscommunication getting out of it, because he wants to keep turning. My fours are a wee bit of a slalom. But it’s good. And as I’m walking out, the scores go up: 70%. Third place, by just 0.4%. We are in it!

I am beside myself. Cadeau doesn’t understand what all the fuss is about—of COURSE he was brilliant, why are we all treating this like a big deal—but he cheerfully gets lots of smooches from everyone, especially three of his amazing syndicate members, who’ve made the trip to watch him dance.

Man, oh man, do I want to celebrate, but I have to show again tomorrow, so instead I get a workout in, take Cadeau out for a graze (the bugs at Lamplight are legendary, so he’s head-to-toe dressed in his Bow Horse fly gear), and help my friend Lauren Chumley move some of her horses in. I take my book manuscript to dinner because I’m so behind on it.

While trying not to spill salsa on the notes my brilliant friend and syndicate member Stacy Curwood has written for me, I watch the storm clouds roll in. And I’m glad we’re all under cover when they let loose, because they let LOOSE. Cadeau is stabled in Tent 1, as are a huge number of other very, very famous horses, and as I watch their team of grooms scramble to keep the inches of rain out of their horses stalls, I’m comforted to know that there is no amount of money, staff or time that can prevent horses from being horses, and nature from being nature.

Tuesday

Between the weather and the newfound pressure of expectation—boy, oh boy, is it easier to do this when you’re a scrappy insurgent rather than sitting on top—I did not sleep well. And I drew the last slot in the class, which is amazing, but adds a whole ‘nother level of anxiety. But as always, once I’m on the horse, all that stress slips away. It’s me and my best boy, and I’ve done my best forelock braid ever, AND I Wordled in two. This is going to be a good day.

“Once I’m on the horse, all that stress slips away. It’s me and my best boy, and I’ve done my best forelock braid ever, AND I Wordled in two. This is going to be a good day.”

I get on wondering if Cadeau will be tired at all, whether he slept well, whether I should have changed the plan in any way. When I put my leg on to begin his warm-up trot, and he holds his breath and scoots with a sassy little tail toss, I get my answer: Oh no, we’re on fire today. But we have been pals a long time, he and I, and he cheerfully lets me channel that heat.

He holds his breath again as we’re going around the ring, but I’m ready for it. In the warm-up we pushed the envelope with the trot just a wee smidge, just asking for a little more expression and power but without going over the line. It’s a balancing act, but he lets me do it. Arms long, contact thinking forward. I have a right leg, not just a left. The extended trot still isn’t where I want it, and he thinks a brief impure thought at the beginning of the zig zag, but he lets me call him back to order with ease. I have time. I have time. I have time.

And I have a sore face by the end, because he just feels so damn good I can’t stop smiling. The score goes up—another 70%, and this time I take second. Holy expletives!

More hugs, more carrots for the best horse ever. And then out to dinner with my amazing owners, where I indulge in some lovely sparkling wine because HECK YES. Cheers!

Wednesday

It’s a day off from competition, so I hop on Cadeau first thing and go about the Very Serious Business of walking on the buckle and trotting a handful of 20-meter circles with his head on the floor. His chores are done, he’s walked in the arena, he’s hacked around the arenas, and he’s been put away and sufficiently snuggled, all by 9 a.m. I watch the entirety of the Grand Prix class with Sabine Schut-Kery, who I adore and never get to see, and I forgive her for beating me in the Intermediaire classes because she lets me sit at her cool kids’ table so I feel very important and fancy.

And then… it’s only 10:45 a.m. So I visit with more friends, and then it’s only 11. So I feed Cadeau lunch and pick out his stall once more, and then it’s only 11:30 a.m. So I go back to the hotel, and I work out, and I get a pedicure, and then it’s only 2 p.m. So I take a nap. (Who am I?!) Then it is finally time to head back to the show to take Cadeau out for his afternoon graze and feed him dinner, but it is only 4:30 p.m., so I nip back to the hotel and shower and put on a cute dress (another thrift shop find, $11, slay) and it is FINALLY 5:30 and time for action: another competitor’s party. I meet even more amazing people, and see even more amazing friends, because Festival has so many classes that the divisions are quite staggered; I’ll be done competing before some divisions even begin, and most folks didn’t even show up until Tuesday.

Night check and bedtime come and go. I’m waiting to get nervous, and I’m bizarrely not. Because really, I do feel like I’ve already won. Mission already way, way accomplished. For all of my joking-not-joking about liking big hairy ribbons, I’m really, really proud of this horse, and the show we’ve had up until this point, and I’m really, really zen about whatever happens next. Apparently another of 40’s gifts to me is finding some perspective. That’s a nicer gift than not being able to sleep after a glass of wine. Thank you, 40.

Thursday

No questions about it today: We stick to the plan. No, I do not need to ride Cadeau this morning in any capacity, even though we don’t compete until this evening, and while I’m not BAD nervous, I am certainly eager, and I need to find ways to keep myself from chewing off my own arm. I give him a bath and a graze, I work out, and I watch a bit. I pack as much as I can, because I ride at 4:55 p.m., with the awards ceremony scheduled for 6:30-ish, and then I need to pack everything into the trailer such that I can bolt out the door pre-dawn the next morning. But because I still need to show, there is basically nothing to pack. I listen to my freestyle music ten thousand times. Olivia’s had to fly home, but she’s going to warm me up via FaceTime (because my dumb self forgot the stupid Pivo, but fortunately one of my amazing owners and a professional groom friend offer their services as human tripods, so I test my technology once, and I’m set.

And then it’s go time. Cadeau is mentally one hundred percent but a little physically tired, which can sometimes be a scary combination. But good grief, is he ever a little warrior when the chips are down. I remember to hit an extended trot in my warm-up, so I maybe won’t get run away with quite so much in the ring. I practice my first few movements of trot in, halt, trot out, and immediately half-pass left; it’s not such an easy sequence, and I don’t know why I made my freestyle this way, but it’s too late for that regret now. And then we’re in.

I do, in fact, blow my entrance. For a girl who’s spent years trying to apply more right leg, I do so with gusto, and poor Cadeau thinks I’m calling up the canter. But we fix it, and we move on, and everything else is spot on. I finish on a 72%, and with two more riders to go, I’m briefly in the lead. (I have someone take a picture of the Jumbotron while I am. Yes, I am that guy.)

And then, Tom Petty, the waiting is the hardest part. Class leader Sabine goes right after me, and it’s a shutout. But it was a neck-and-neck race for reserve champion, and all the riders are gathering for the award ceremony, and I’m catching up and chatting and putting Cadeau’s polo wraps on trying not to freak out, waiting for someone to walk up to me holding one of two colors of ribbon. And even though my face is so, so sore from almost a straight week of grinning that I think I can’t grin anymore, when my squad walks up holding the red one, I can’t stop beaming. We did it!

The rest is a blur. Cadeau is remarkably civilized in the awards ceremony until we have to canter around, and then he briefly demonstrates how much power and elasticity he has in his back. My team of owners takes him from me so I can sprint over to the media tent for an interview, and then I bolt back down to the barn to load up the truck full of everything to take back to the trailer.

Syndicate members Sloane Rosenthal and Leslie Harrelson have put Cadeau away and smothered him in love, and it’s 7 p.m. before we finally crack open the champagne and then to a quick dinner. I want to be able to really celebrate, but my alarm is set for 3 a.m., because I am going to drive home all day, losing an hour in transit, and then naturally I have a student at a Virginia show at 9:30 a.m. Saturday morning. So we toast, and we hug, and I try and get to bed, but the adrenaline is still pumping, and my phone is blowing up and finally, finally, sleep takes me.

All too quickly it’s…

Friday, Aug. 22

It’s 3 a.m., and I’m up and at ‘em again. When I get to the barn, Cadeau is out—I mean OUT, flat out, carcass time OUT—and I have to poke him a few times to get him up. I’ve learned one of this week’s lessons, and I feed him his breakfast grain before I try to poison him with tummy paste, so he does actually eat.

But then he’s really quite mad when I go to load him, and says NOPE for a few minutes before finally resigning himself to his fate. I am so, so sorry, I keep telling him. This day is going to suck for you, and you were just so amazing, and this is just how it’s going to be. I can hear him rolling his eyes all the whole way home.

The traffic and weather gods are both with us, and we cruise home in a blistering 12.5 hours. I’d left my car at the dealership to address a minor recall issue, with their promise that they’d have it delivered to my farm before today… and at 6:30 p.m. I’m frantically calling their answering service, desperately hoping someone can come and retrieve me, because of course, they have not delivered the car. Eventually I’m rescued, and I finally come through my front door at 7:30 p.m. to a pile of mail dwarfed only by my pile of laundry. The top envelope? A questionnaire for jury duty.

Well, being a rockstar was fun while it lasted. I set my alarm so I can get to Morven Park’s dressage show bright and early the next day. Back to reality!

Lauren Sprieser is a USDF gold, silver and bronze medalist with distinction making horses and riders to FEI from her farm in Marshall, Virginia. She’s currently developing The Elvis Syndicate’s C. Cadeau, Clearwater Farm Partners’ Tjornelys Solution, as well as her own string of young horses, with hopes of one day representing the United States in team competition. Follow her on Facebook and Instagram, and read her book on horse syndication, “Strength In Numbers.”

The post A Week In The Life: The US Dressage Festival Of Champions appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Throwback Thursday: Bold Minstrel Was The Horse Of The 20th Century appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Born in 1952 in Camargo, Ohio, Bold Minstrel was by Thoroughbred stallion Bold And Bad out of Wallise Simpson, who was the result of a test breeding of an unknown mare to a young Royal Minstrel. William “Billy” Haggard III purchased Bold Minstrel as a 5-year-old.

While Haggard never had any formal training, he competed at the highest levels of sport. From steeplechasing to show hunters to eventing, Haggard proved himself over and over again as one of the top riders of his time.

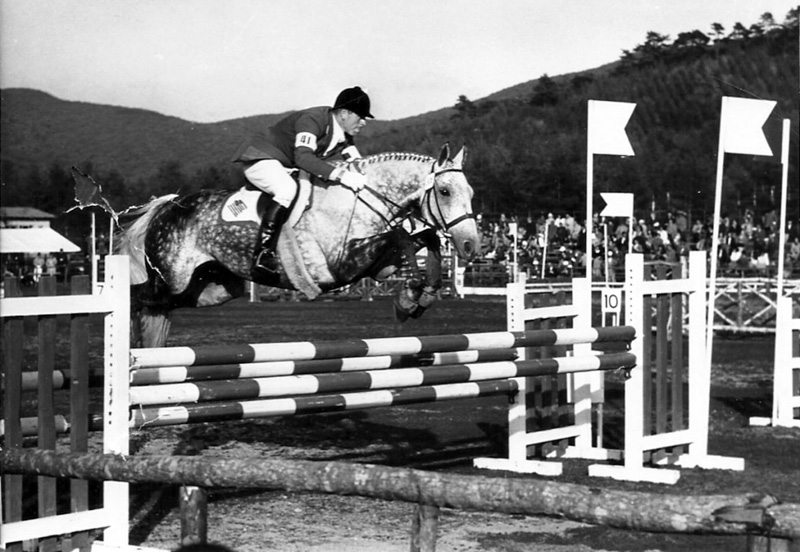

William Haggard and Bold Minstrel.

Topping out at 16.3 hands, the stunning gray was such an easy keeper that he was affectionately called “Fatty.” Bold Minstrel’s career actually began in the hunter ring, and his stunning looks and lovely jump garnered him dozens of ribbons in the conformation divisions across the country, including a reserve championship at the National Horse Show (New York). Eventually, though, Haggard switched his focus to eventing.

In 1959, Haggard and Bold Minstrel tackled the Pan American Games in Chicago, Illinois, and helped the U.S. team win the silver medal in addition to placing ninth individually. Four years later, they were sixth individually in São Paulo, Brazil, and clinched the team gold. Between those two Games, Haggard still campaigned Bold Minstrel in the hunter ring.

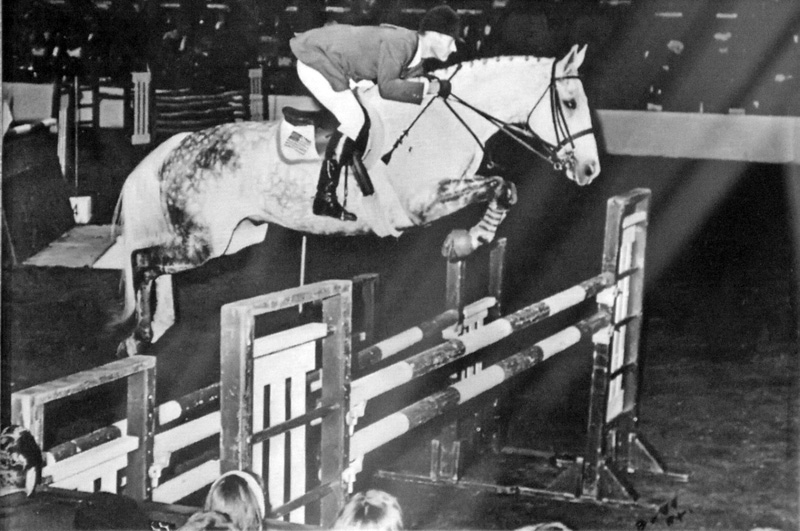

William Haggard and Bold Minstrel showing in the hunters at Devon. The pair competed successfully in the hunters in addition to eventing. Jimmy Ellis Photo

While it seemed like the pair would be a shoo-in for the Olympic Games in Tokyo the following year, the selectors did not include them on the team. However, when J. Michael Plumb’s mount, Markham, had to be euthanized on the flight over, Haggard loaned Bold Minstrel to the veteran rider.

“Michael Plumb, as can be imagined, was at a tremendous disadvantage having to compete in the Olympic Games after only riding the horse for two weeks before hand,” wrote teammate Michael Page in the Nov. 20, 1964, edition of The Chronicle of the Horse. “However, from the excellent dressage ride on the first day, to the ‘must’ clear round to protect the medal on the last day over a trappy jumping course, Plumb and Bold Minstrel never once shook the confidence placed in them.”

Michael Plumb and Bold Minstrel in the show jumping at the 1964 Olympic Games.

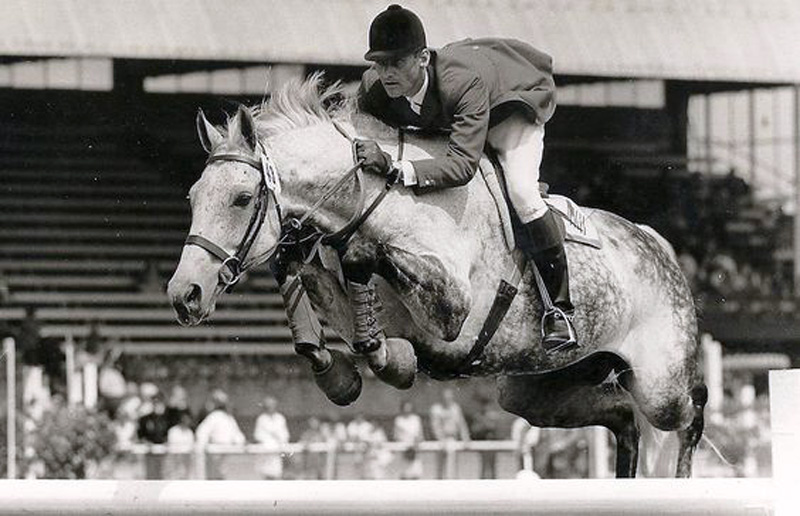

Since Bold Minstrel was only 12 after his first Olympic Games, where he helped the team earn silver, Haggard decided to continue to campaign him. However, as the horse had already reached the highest levels of two sports, he loaned him to Bill Steinkraus.

Steinkraus rode the gray gelding in numerous international show jumping events between 1964 and Bold Minstrel’s retirement in 1970. They won more than a dozen major competitions, including the Grand Prix of Cologne (Germany). In 1967, they also set two puissance records at the fall indoor shows, jumping 7’3” at the National Horse Show.

Bill Steinkraus and Bold Minstrel.

“It takes something special to make me wear a white tie and tails to a horse show, but the old Garden was special,” wrote Jimmy Wofford in the April 2008 issue of Practical Horseman. “I was willing to dress up like the Phantom of the Opera to watch quality show jumping. It was even more special when Bill Steinkraus came out of the corner next to me on his way to a 6-foot 7-inch puissance wall. With his uncanny eye for a distance, Bill saw a steady seven strides to a deep distance. This is just what you want when you are about to jump a big puissance wall. Unfortunately, Fatty saw a going six, grabbed the bit and opened up his stride. The book will tell you that you can’t jump that big a fence from that big a stride, but Fatty left it standing, much to Bill’s relief.”

Bill Steinkaus rode Bold Minstrel in the 1967 Pan American Games in show jumping, where the gelding won yet another team silver medal. They also set several puissance records in that same year. Budd Photo

Bold Minstrel competed in his third Pan American Games in show jumping in Winnipeg, Manitoba, that same year and, again, earned the team silver. That medal solidified Bold Minstrel’s epic career, making him the only horse to have medals in three Pan American Games and one Olympic Games in two disciplines.

Bold Minstrel continued to compete well into his late teens and eventually retired in 1970 at 18 years old. That year, he won three times at Lucerne (Switzerland) and won the Democrat Challenge Trophy at his old stomping grounds, the National Horse Show. After he retired from competition, Haggard took him home to his farm and foxhunted him.

Bill Steinkraus showing Bold Minstrel.

“This gray horse gets my vote as the greatest horse of the 20th century,” wrote Dennis Glaccum in the Dec. 24, 1999, issue of the Chronicle, where Bold Minstrel was named one of the most influential horses of the century. “He stands heads and tails above any other horse I have observed in my lifetime.”

In 2011, COTH writer Coree Reuter embarked on a quest into the attic at the Chronicle’s office. While it’s occasionally a journey that requires a head lamp, GPS unit and dust mask, nearly 75 years of the equine industry is documented in the old issues and photographs that live above the offices, and Coree was determined to unearth the great stories of the past. Inspired by the saying: “History was written on the back of a horse,” she hoped to demystify the legends, find new ones and honor the horses who have changed the scope of everyday life. This article was originally published Feb. 2, 2011.

The post Throwback Thursday: Bold Minstrel Was The Horse Of The 20th Century appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Opinion: We Can Remedy The Scourge Of Overuse In Horse Showing appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Unfortunately, the town hall failed to address one of the most significant root problems of horse abuse: the overuse of horses in jumping-based competition for economic and personal gain.

Most USEF stakeholders have a conflict of interest in this discussion: The more that horses compete in USEF competitions, the more money is made by competition managers, trainers, riders, owners, veterinarians and USEF. Each entity benefits economically from horses being shown more, so there is an inherent bias in avoiding a solution to the overuse problem.

Too Many Competitions, Too Many Classes

USEF rules do not restrict the number of classes that a hunter/jumper horse can compete in per day, week, or month. The recently updated GR Subchapter 8-F Welfare of the Horse—specifically GR838.1—addresses overuse and unethical treatment of horses. But without an objective way to assess what constitutes overuse, it is a meaningless rule subject to varying interpretation. The matter is only really brought to the fore after a horse is injured. USEF maintains a record of every rated class a horse contests, so competition frequency can easily be monitored.

A 2023 USHJA rule change proposal attempted to cap the number of over fences classes horses could participate in at eight per day, a shockingly high number. However, due to challenges in execution and broad disagreement on what the limit should be—including whether it should vary based on fence height, class type or competition format—even that proposal was ultimately withdrawn following extensive debate at the USHJA Annual Meeting. It’s not surprising the proposal was deep-sixed, but it is now high time for USEF to enforce meaningful limits on the number of classes in which horses can compete on a daily and monthly basis.

The economics of the sport make addressing competition overuse challenging, because it is not in the interest of many of the parties involved to introduce class limits. Show managers make more money on entry fees with each class a horse enters, so it’s hard to see them supporting class limits.

Trainers make more money with each show a horse attends and each day a horse shows, so one can’t expect them to support class limitations. (Plus, when a horse becomes injured, the trainer’s quest to buy a replacement often begins, once again to their economic benefit.)

Veterinarians are also complicit in competition overuse because of the immense pressure they face to get horses back in the ring. Owners often prefer not to hear that their horse needs a few months off when an injection or other treatment can get them back competing more quickly. A veterinarian is somewhat beholden to the owner’s demands to achieve results fast. If a veterinarian is reluctant to treat the horse aggressively, the owner may well find another veterinarian who will. One cannot, therefore, expect veterinarians to support class limitations readily.

There is no union for horses, but there are examples of fair horse usage rules already in place, including New York City carriage horses, who are not permitted to work for more than nine hours in any 24-hour period (including waiting time). At U.S. Dressage Federation-recognized competitions, governed by USEF rules, horses are limited to a maximum of three classes per day from intro through fourth level and a maximum of two classes a day at Prix St. Georges level and above. Pressure to overuse horses is a recognized problem for which some practical solutions have already been found, including by USEF in certain disciplines.

Like other professional sports, there is generally no longer an off-season for horses. National and international competitions are held year-round, unlike in the past when the show season wound down after Toronto’s Royal Horse Show in November and restarted in Florida in February. During the winter, one- and two-day schooling shows were the only things on the calendar. Now, there are high-level shows all year. Keeping a horse out of the ring or resting it for a few months is hard when there are multiple pressures to show. Yet that is exactly what needs to happen.

Supply-side economics predicts that the greater the quantity of classes available, the more classes horses will compete in. In addition, the more shows a horse competes in, the more competition fees USEF receives. USEF year-end awards also create pressure to overuse horses in competition. More placings mean more year-end points. The Fédération Equestre Internationale ranking list further exacerbates horse overuse because riders must constantly compete to stay high enough in the rankings to qualify for the most prestigious events. Even for our top riders, the pressure to stay in the ring is immense.

For those fortunate riders who have multiple horses, overuse is less of an issue because they can rotate their horses among shows. But for most others, there is a necessary tension between what is right for the horse and what the rider—who needs to gain experience, win year-end points, and/or maintain a ranking list position—wants.

Fair Treatment, Fair Maximums

However, horses have limited life spans. The length of a horse’s competitive career depends not only on its physical conformation, but even more on the quality of its management throughout its active years. Overuse is a significant cause of injury that curtails many equine athletes’ careers. The show environment is challenging—both physically and mentally—and simply getting to competitions can also include long journeys for our equine friends.

Clearly, there should be some limit on the number of competitive rounds a horse is allowed to do; it is both ethical and responsible. But how might that work? There are ways that USEF can encourage sensible and reasonable limitations on equine competitive stressors. Developing a rule that accommodates the need to show while capping the number of classes the horse competes in would address the issue.

Most USEF stakeholders have a conflict of interest in this discussion: The more that horses compete in USEF competitions, the more money is made by competition managers, trainers, riders, owners, veterinarians and USEF.

When the USHJA withdrew the class-capping rule in 2023, one sticking point cited was that because entries are submitted in advance, some horses are entered in more classes than they will actually contest and then scratched from some closer to show day. However, USEF tracks entrances into the ring and the subsequent results, which eliminates confusion on this issue.

At a minimum, USEF could discourage overuse by tracking the daily number of classes and monthly number of shows a horse contests. It could decide that points gained outside of reasonable use parameters would not count toward year-end or ranking points, or combinations could be ineligible for prize money. It could notified owners if their horse exceeds fair use limits.

Obvious overuse is currently prohibited by USEF regulations under cruelty and abuse prohibitions, but enforcement is on a case-by-case, subjective basis and is after the fact, which is unfortunate for the horse involved. Encouraging appropriate use with these measures strikes a decent balance but remains a retroactive solution.

Class Limits Are The Way Forward

If we really want to tackle the overuse issue, class maximums are the way forward. So, how might this work? A greater number of classes would reasonably be permitted at the lower levels; for example, a pony competing in hunter and equitation classes can comfortably contest more classes per day than a grand prix jumper. A basic formula could be introduced to govern the various jumping levels, with varying limits on permitted class numbers.

Reasonable maximums for the following could be codified as follows:

- Number of shows in a month

- Number of consecutive days of showing

- Number of classes per day based on course height

For example, a general restriction of three shows per month could be implemented, with a maximum of three consecutive days of showing permitted, and—dependent on fence height—a maximum number of jumping classes per horse per day:

- Course above 1.30 meters: Two classes

- Course 1.20 to 1.30 meters: Three classes

- Course below 1.20 meters: Four classes

These are not draconian limitations; they would still allow horses to compete in a generous monthly maximum of 24, 36, or 48 classes, depending on the level. We could also hammer out a fair formula for horses competing across the different levels. While there is room for debate, the principle is simple: we can’t keep pounding our horses into the ground.

It’s high time we challenged ourselves to ensure horse welfare is safeguarded from all angles. Even if instances of overuse are few, for affected horses, it is unacceptable. We all have differing experiences, so active participation in USEF’s town hall meetings is essential to gain perspective and opinions from peers. Limitations on competitive rounds may provoke some pushback, but it moves the welfare dial in the right direction. Horses are not bicycles whose parts can be replaced if worn out or broken. They deserve to have meaningful protections against overuse, and USEF is best positioned to spearhead this progressive step.

Armand Leone of Leone Equestrian Law LLC is a business professional with expertise in health care, equestrian sports and law. An equestrian athlete dedicated to fair play, safe sport and clean competition, Leone served as a director on the board of the U.S. Equestrian Federation and was USEF vice president of international high-performance programs for many years. He served on the USEF and U.S. Hunter Jumper Association special task forces on governance, safety, drugs and medications, trainer certification, and coach selection.

Leone is co-owner at his family’s Ri-Arm Farm in Oakland, New Jersey, where he still rides and trains. He competed in FEI World Cup Finals and Nations Cups. He is a graduate of the Columbia Business School in New York and the Columbia School of Law. He received his M.D. from New York Medical College and his B.A. from the University of Virginia.

Leone Equestrian Law LLC provides legal services and consultation for equestrian professionals. For more information, visit equestriancounsel.com or follow them on Facebook at facebook.com/leoneequestrianlaw.

The views expressed in opinion pieces are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of The Chronicle of the Horse.

The post Opinion: We Can Remedy The Scourge Of Overuse In Horse Showing appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Camp, Learn, Save: Returning To The Jumper Ring Thanks To A UDJC Show appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Well, it turns out it’s a little harder than I thought to stay away from the sport that got me addicted to this lifelong horse habit in the first place. As time has passed, and I have moved out of school and into my career, now that I feel like I have a little more financial stability to spend money on extra things, I find myself absent-mindedly scrolling through lists of horse shows and horse trials in my area, thinking more and more about how it could be fun to go jump around somewhere other than my arena at home.

I board at a self-care facility and don’t have a trainer in Wisconsin, so I figured going to some sort of competition was a good way to check in and see whether the small amount of skill I have managed to acquire in my 31 years of life was being maintained to a reasonable, up-to-snuff standard—“snuff” in my mind meaning, “Can I jump around a three foot course without scaring anyone watching?”

Around that time is also when I started seeing these funny little videos come up on my Facebook feed. You’ve probably seen them too: They feature German rider David Reichert speaking to the camera about a new show series he has created called UDJC, the United Dressage and Jumping Club. Two lines in the video caught my attention in particular; the first was a claim that UDJC “offers recognized horse shows, with double the fun at a fraction of the cost, in the disciplines of dressage and jumping.”

That got me curious for a couple reasons. First of all, I found it interesting that the shows featured dressage and jumping classes. I learned after speaking to David at the Aug. 2 horse show that he very intentionally set it up this way. When David was growing up learning to ride in Germany, he said it was expected that riders learned both dressage and jumping.

“All of us were expected to do both until we could ride around a third level dressage test and a [1.20-, 1.25-meter] jumping course,” David explained. “Then we would start to specialize in one of the other.”

When David moved to Texas in 2020, he was surprised how separate the two sports were kept in the United States, and he felt it was to the detriment of developing riders’ skills. Combine that with the eye-popping invoices he was seeing people pay to compete in American horse shows, and David decided he needed to do something about it.

So, in January, he produced the first UDJC horse show in Texas, complete with very entertaining promotional videos like those I saw on Facebook. (Fans of funny horse people on the internet will know The German Riding Instructor; he’s David’s friend and inspired many of the UDJC videos.)

I understood the concept for the show, but I did still wonder just how fractional the prices of these shows really were. I did a Google search for UDJC shows in my area and then pulled up an entry form on HorseSpot.net. Sure enough, it was indeed fractional: The trailer-in fee would be $30, each class would cost $35, with anywhere from $100 to $250 dollars in prize money awarded even in 0.65-meter classes. I could also choose between a 30-day trial membership for myself and my horse ($10 for the horse, $30 for me), or I could get a lifetime membership for my horse for $175, and an annual membership for myself at $90. So far so good. These are the kind of prices I am looking to pay for a horse show.

The second line in the video that I found interesting was David’s statement about how the jumper classes would be judged. He explained all classes under 1.0 meter would be judged for style not speed, “because no one should be racing through 70-centimeter courses with 14 jumps and two combinations against the clock.” The video explains riders are given a score, from 1-10, based on how well they rode the course, with 0.5 points deducted for each rail down.

I couldn’t agree more. We all know the scariest place at a horse show is the warm-up ring for the 0.85 class, and I have seen many a rider go into those classes and gallop around at breakneck speed, narrowly avoid flipping their horse over an oxer they left two strides too soon for, and be rewarded with a win if they managed to keep the fences up. I don’t want to fly around like a maniac, but when the fences are that low, if you are not willing to match these rider’s speed, you’re not competitive.

I’m glad some of the lower jumping classes at USEF-recognized shows have switched to an optimum-time format, because that definitely incentivizes better riding, but this UDJC concept of getting a score similar to an equitation class from a judge representing how well I rode the course was intriguing to me.

So I decided to take the leap and sign up for the nearest UDJC show to me, which was held at Oaklawn Farm in Wayne, Illinois, a few minutes down the road from HITS Chicago at the larger Lamplight Equestrian Center.

I still meant what I said a few years ago about wanting to continue trail riding and camping with my horse, so after looking up the address for the show, I started Googling to find the nearest campground that allowed horses. The answer was about 20 minutes away, at the Burnidge Forest Preserve. For $20 a night I could park my truck and trailer and camp with my horse. I had water, electric outlets, a fire pit, hitching posts, and nine miles of trails around the property to explore.

So, after working the full day the Friday before the show (all of the classes for the show were on Saturday and Sunday—bless up for the working amateur), I grabbed my dog and loaded the trailer at 6 p.m. to make the two-hour drive to the campground. I arrived a little after 8 p.m. and got my horse Moji set up in his spot; in an ideal world, I prefer to camp at sites with paddocks, but this one only had hitching posts where you could rig a tie line. Luckily Moji couldn’t care less, so I strung up the line, secured his rope halter to it with a safety knot, and he was good to go.

Let me say, I know what some of you may be thinking at this point: There is no way in hell my show jumper would tolerate camping overnight, tied to a line. I could have gotten a stall at the UDJC show for $100, but I both enjoy the camping experience and loved that this show gave me the ability to save money if I wanted to. With no requirement to stable on grounds, I could save money on both a hotel and a stall by camping.

This has always been my beef with horse shows: I can be frugal with where I keep my horse (self-care board), I can be frugal with how I take lessons and train my horse (haul in, look up exercises to do at home online), I can be frugal with where I sleep at night when I’m at a horse show (a mattress in the gooseneck trailer tack room). But I cannot do anything to lower the cost of entering a class, nor the cost of a membership fee, and many USEF-recognized shows either don’t allow haul-ins or charge so much for them that you may as well get a stall.

I have no problem with people wanting to horse show very differently than I do. You can get a stall and a grooming stall, stay in a nice hotel, board at a full-care facility, and pay a braider and a groom to get your horse ready, if you want. I have a problem with the cheapest option for a person willing to put in the work and do everything possible to make a show affordable still being a $1,000 horse show bill.

So here was an option that gave me that freedom—and turned a horse show weekend into a two-for-one camping trail ride. UDJC uses HorseSpot.net as its show software, and the start times for classes are updated throughout the day. So when my Sunday class wasn’t scheduled to start until noon, I slept in, made some coffee, moseyed around the campsite with my dog, and then, while still wearing my oversized T-shirt and pajama pants, tacked up Moji for a walk around the trails to stretch his legs. Sure beats sitting on a trunk in front of my stall waiting for my class to start! Around 11:20 a.m, I loaded him to make the 15-minute drive from the campground to the show.

The show itself served exactly the purpose I needed it to, which is to say it was both fun and made it very apparent what I needed to go home and work on. Back in 2019 Moji and showed in the 1.0- and 1.05-meter adult jumpers, but since we were out of practice, I decided to do the 0.75- and 0.85-meter classes on the first day of the UDJC show, and the 0.85 and 0.95 the second day. USEF ‘r’ hunter and hunter seat equitation judge Kathy Davidson was judging our classes, and along with assigning a style score, judges at UDJC shows give immediate feedback to riders after their rounds.

So for each of our classes, Moji and I would finish our round, make a circle, and then walk over to the judge’s booth to get a quick lesson on what we did right, and what we needed to work on. As someone who doesn’t have a trainer at home—or at the show with me—this was so helpful.

Kathy commented on Moji’s big stride and how I needed to package him together more as the course went on and not let him get so strung out. She also suggested I work at home on jumping from deeper distances, because she could tell we both preferred the long distances, but we needed to have both options in our toolbox.

I remember interviewing Anne Kursinski back in my days as a full-time Chronicle reporter, and her saying that a horse show is supposed to be the test you take after sitting at home and doing your homework for a few weeks or months. Are the things you’re working on paying off, how does your riding stack up against your peers, and can you apply everything you’ve worked on at home in a new environment with some pressure?

From that perspective, my UDJC experience was the perfect horse show. Not only is it testing what you’ve been working on at home, you get graded by the teacher in real time and told how you did, and how you can improve! Getting a ribbon for not dying in the 0.65 class you chipped and flew around isn’t really testing your skills or making you a better rider. Being judged on your style and skills and only rewarded when you ride in a way that is safe and effective and kind to your horse makes a lot of sense to me, and it makes doing well in a class feel a lot more rewarding. I love that there is a place I can go and compete and be rewarded for riding well at lower heights, and I only have to spend a couple hundred bucks to do so. (Exactly $220, if we want to be precise.)

I am totally stoked that David has started these shows, and I can’t wait to hit up the next one in Illinois.

Ann Glavan is an associate attorney with LawtonCates S.C. in Madison, Wisconsin. Before becoming an attorney, Ann spent four years working full time for The Chronicle of the Horse.

The post Camp, Learn, Save: Returning To The Jumper Ring Thanks To A UDJC Show appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Make Space In The Show World For Kids With More Heart Than Budget appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>She comes from a big, chaotic, love-filled family with five kids, a small farm, and a passion for horses that runs deeper than our pockets.

She doesn’t have a six-figure horse or show in the top circuits. But she’ll muck stalls until her arms throb. Cobweb for hours. Scrub tack until her hands are bright red. She’ll ride anything with a heartbeat and say thank you for every opportunity.

She works two jobs on top of helping at our own farm. Doing barn chores and working retail at a tack shop.

Kids like her are ones I hope this industry keeps making space for. Because it’s not always easy to be that kind of kid in the horse world.

Not long ago, she left a barn that was like home. The place where she found not just friends and family, but her courage and her confidence with a trainer who loved her and believed in her for three years.

We left not because we wanted to. We left because staying wasn’t financially feasible. Continuing to lease long term on top of boarding wasn’t sustainable.

When we talked with her trainer about our situation, we were honest. We explained that we needed to begin looking for a more economical path, most likely moving her home to ride, and perhaps finding a working student-ish position. Something that would let her keep chasing her dreams of showing without the nail-biting financial pressure.

It broke our hearts. But her trainer was incredibly understanding. She gave us time and support. “There is no rush. She can ride here while you explore options.” She let my daughter leave her trunk. She helped us try horses we could bring home. But for months, nothing quite fit. Our budget made horse shopping stressful rather than exciting and full of promise.

Then, her trainer presented an affordable short-term lease that could hold us over for the winter while we continued to get our ducks in a row. A kind, steady 2’6” horse who turned out to be exactly what she needed.

She was thrilled when we told her, after months of horselessness.

“Thank you!!! I’m so excited to bond with a horse again,” my kid texted me with celebratory emojis.

She understood this was her last opportunity to board at her current barn. She relished every minute of that lease. She built confidence in herself and her riding, showing three times and winning tricolors at every show with her trainer’s support. But the ribbons weren’t the point. The point was that she giggled again. Made silly jokes. Came back to life.

And when the lease ended, something shifted. Instead of being consumed by sadness, she was thankful. Thankful for the foundation her trainer had laid for her riding future, for her caring. And thankful for all the memories: Halloweens bobbing for apples, jump-painting parties, heart-to-heart chats in the tack room.

She was finally as ready as she would ever be to say one of the hardest goodbyes of her 15 years.

So, we moved her tack and her trunk home, and I found her a project pony. She rode in our backyard field while the weather was nice. But even as I helped her ride and rebuild, I knew it wasn’t enough for her. Though she was grateful to ride, her light dimmed again.

Because this girl wants her riding and horsemanship to improve. She wants to learn all the things. This girl doesn’t just love horses. She loves the barn. The teamwork. The sense of purpose.

And kids like her, especially teenage girls fighting the loneliness of school hallways, the pressure of social media—they need a second home. A community.

So, I reached out to a few local trainers, including a young trainer who was always kind and friendly to us. Someone I thought might give a kid who is all heart a shot. And when she said, “Have her come for a lesson. We can talk,” I felt like a giddy child.

Still, we were nervous. My daughter wasn’t done grieving the loss of her last barn, still missing her trainer and her barnmates. On our way to that first lesson, she was quiet in the car. “What if she doesn’t think I’m good enough?” she muttered, barely able to say it aloud.

“She’ll see you,” I told her. “She’ll see you’re a hard worker. She’ll see who you are.”

And she did.

After the lesson, the trainer turned to me and said, “So what are you thinking?”

I was honest. “We have five kids. We’re not a big-budget family. We’re hoping she can work off as much as possible. She wants it so badly. She will work hard.”

She nodded, understanding rather than judging: “I like helping. We’ll figure it out.”

And just like that, someone flung a door wide open when it felt so many doors were locked shut.

Now, my daughter rides with joy again. She tacks up countless horses. Hacks whatever she’s asked with a grin. Stacks saddle pads, still warm from the dryer. Constantly asks, “What else can I help with?” Because she wants to be useful. She’s proud to belong.

Though the expectation set was to work at least four hours over three days per week, spoiler alert, my kid chooses to help nearly every day. Not because the trainer expects it, but because it fills my daughter’s soul.

“It’s making me better, Mom,” she tells me when she returns home grimy, tired, and fulfilled.

She is also proud and grateful that she travelled with her trainer to HITS-on-the-Hudson (New York) for three weeks to groom. She showed twice as well—truly a dream-come-true for a kid who rarely had the opportunity to show rated, let alone at a big venue.

And I can’t overstate what these kinds of opportunities mean to her. To a kid who sometimes feels invisible. To a kid who’s not sure where she fits or if she’s good enough. Who’s been told by the world that she needs trendy clothes, clearer skin, more followers, more money.

Being useful at the barn makes her feel beautiful. Complete just as she is.

There are thousands of kids just like mine all over this country. Kids who are addicted to horse life. Kids with tenacity and grit. Maybe they don’t own horses. Don’t have connections. Aren’t the slickest riders.

But they’re kids who deserve to be seen.

I get that not everyone can offer a free ride. Not every trainer can take on working students. I truly understand the reality of trainer-life, how hard it can be to pay the bills. How difficult it can be to find the time. But if you can offer opportunities, even just a few, you will change lives.

Because when you believe in a kid like mine, you’re not just giving her a horse to ride. You’re giving her a reason to believe in herself. You are giving her a future.

And you may just be changing the future of the sport.

Jamie Sindell has an MFA in creative writing from the University of Arizona and has ridden and owned hunters on and off throughout her life. She is a mom of five kids, ages 4 to 15. She and her family reside at Wish List Farm, where her horse-crazy girls play with their pony and her son and husband play with the tractor.

The post Make Space In The Show World For Kids With More Heart Than Budget appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post My Trainer And Barnmate Are Having An Affair. What Should I Do (If Anything)? appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Have a question for Stable Sage? Email it to coth.advice@gmail.com. We reserve the right to edit your submission for clarity and length, and we promise to keep it anonymous.

Dear Stable Sage,

I’m an adult ammy who has picked up on the fact that one of my barnmates is having a thing with our trainer. The flirty vibes are undeniable. And when we’re on the road, I’m 99.9% sure they’re ending up in each other’s hotel rooms.

We’re all grown adults roughly the same age, so at least there’s that. But they are both married. At first, I told myself I didn’t care. Like, “Whatever. Not my marriage, not my bed. I’m just here to ride my horse.”

But the truth is, it does get under my skin. And I hate that I’m expected to just ignore it.

Do I confront it? Swallow it? Switch barns? I don’t want to be dramatic, but I also don’t want to be complicit.

Seeing Too Much and Saying Nothing

Dear Seeing Too Much,

Let’s start with this: You are not overreacting. If it feels off to you, you don’t have to gaslight yourself into silence.

Even if they’re both in open marriages, or in some other arrangement that isn’t yours to question, the issue here is more than just moral. It’s professional. A trainer holds power over resources, attention and the perception of fairness. And power imbalances don’t require a big age gap to be real or damaging.

We’ve all heard the SafeSport horror stories, but here’s the thing: Even when everyone’s a consenting adult, things get messy fast when someone in a position of authority gets personally involved with a client.

So now what?

Decide where your line is.

Some riders can tune out the behind-the-scenes drama if the coaching is solid. Others can’t—and shouldn’t have to. You’re not complicit for staying if your needs are still being met. But you’re not dramatic for leaving, either. Only you can decide whether this barn still works for you.

Let me say this loud for the adults amateurs in the back:

- You deserve a trainer who respects professional boundaries.

- You deserve a barn that feels like a team, not a reality show.

- You deserve to ride your horse without wondering if someone else is getting more because of something going on behind closed doors.

Speak up, if it feels right.

If this is actively affecting your coaching experience or your sense of fairness, you can bring it up directly:

“I’ve noticed what seems like a personal relationship between you and [barnmate], and I want to be honest: It’s made me question whether I’m getting the same level of attention and support. This is a professional relationship, and I need to know I’m being treated fairly.”

You can also name your discomfort in a more general sense. Your own sense of morality has worth, too. And besides, if they’re being shady in this realm, what else might they be morally ambiguous about? A trainer-student relationship has to be built on trust.

Feel free to borrow this script:

“Look, I know I don’t know the details of your personal life, but it’s still uncomfortable to be around as a client, knowing you’re both married and this seems to be happening in a space we all share.”

All you’re doing is expressing how the situation makes you feel in a shared professional environment. If your trainer responds with defensiveness, guilt-tripping or makes you feel like you’re the problem for noticing? That tells you everything you need to know.

You’re not jealous. You’re not uptight. You’re just paying attention.

The post My Trainer And Barnmate Are Having An Affair. What Should I Do (If Anything)? appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>The post Move Over, Barn Rats, ‘Barn Grandma’ Is Setting The Pace appeared first on The Chronicle of the Horse.

]]>Like most stables around the country, my little riding facility in Gibsonia, Pennsylvania, depends upon extra help during summer camp season. The bulk of our counselors are our own teenage lesson students who drag themselves out of bed early a few weeks every summer to help campers glue plastic gemstones to horseshoes, steer school ponies around rainbow-colored plastic cones, and unwrap stubborn string cheese and yogurt tubes at lunchtime.

But this summer, our program has a new counselor. I’ve never had to ask her to put away her cell phone. She’s never arrived at camp with friend or boy drama. She never complains that 9 a.m. is so early. She’s the first one down the driveway every morning and the last one bustling around the barn after all the campers have departed for the day.

Phyllis Frazier is—how do I say this without her killing me?—a bit more “mature” than most of our other camp counselors. She barely clears 5 feet tall, though her spiky gray hair might give her another inch. She has tattoos and a strong Pittsburgh accent and recently celebrated her 70th birthday at an AC/DC concert with her grandson.

Our teenage counselors yell “PHYLLIS!” down the aisle every morning (while they are sipping their coffees and checking their latest snaps on their phones) as she’s undoubtedly bustling around, setting up for the day.

Our horses know that her pockets are full of peppermints, and the ones that haven’t lost stall guard privileges nuzzle her as she walks past.

This summer, she’s brought so much joy and life to all of us at the barn.

A Decades-Long Dream

For as long as she can remember, Phyllis has loved horses.

“I’ve always thought they were so beautiful,” she said.

But raised as the oldest of six siblings, she knew that riding lessons just weren’t in the cards. So Phyllis grew up. She raised a daughter. She married, divorced, remarried and was widowed. She became a grandmother.

She was well into her 60s when she decided that if that dream of riding was going to become a reality, it was now or never.

So she started taking weekly lessons with us in 2021. But two years later, she had a fall in a lesson. Though she—like any die-hard equestrian—climbed right back on, a pain in her back when she re-mounted actually made her nauseous. A trip to the emergency room revealed that she’d crushed several vertebrae and would need to take a three-month hiatus from the saddle. But the real kicker: X-rays also diagnosed her with osteoporosis.

After months in a brace and numerous doctor’s visits to track her progress, Phyllis’ back healed. She asked about returning to riding, and her doctor said that she could return to the sport, if she wanted to.

But—as both her doctor and her daughter reminded her—her bones weren’t as strong as they once were. The older we get, it turns out, the less we bounce. The osteoporosis diagnosis, more than anything, worried her.

Phyllis thought long and hard before making the tough decision to hang up her helmet. She absolutely loved the barn and the horses, but another fall just didn’t seem worth the risk.

But she wasn’t willing to completely walk away from the horses she loved, and after months of hounding on our part, she took us up on our offer to just come and hang out. For almost two years now, she’s been coming to the barn a few times a week to groom and pamper our herd.

She checks our lesson board to see what horses have the day off and rotates through the barn on her visits, currying dirt from coats, applying hoof conditioners and medicated creams to cuts and scrapes, brushing manes and combing out tails. When she’s done, even our retired schoolies look show-ring ready.

Then she walks the aisle, topping off water buckets and filling hay nets.

I learned recently that before she leaves the barn, she photographs the horse she groomed, posting the pictures on her Facebook account so her friends can share in what brings her so much joy.

“Everyone loves seeing the horses,” she said. “They’re always asking about what I’m doing at the barn.”

Student Becomes Teacher

Sometime in late spring, Phyllis was in the stall brushing out Moose’s tail when I paused at the door to chat. She told me how much she loves her time with the horses, and how much happier she feels for the rest of the day, despite being covered with hair and sweat and dirt.

I don’t remember exactly how the topic came up, but I think I joked that if she wanted some serious quality barn time, she was more than welcome to come and help out at summer camp.

“Count me in,” she said the next time I saw her.

She’d found the camp dates on a flyer on the barn bulletin board, she said, and she’d penciled them in on her personal calendar. I wasn’t sure if she knew what she was signing up for and suggested that she plan on coming for the first week to see how she felt about it. If it wasn’t too much torture, I said, she could certainly stay for the summer. She came that first week, and she’s stayed for every camp that followed.

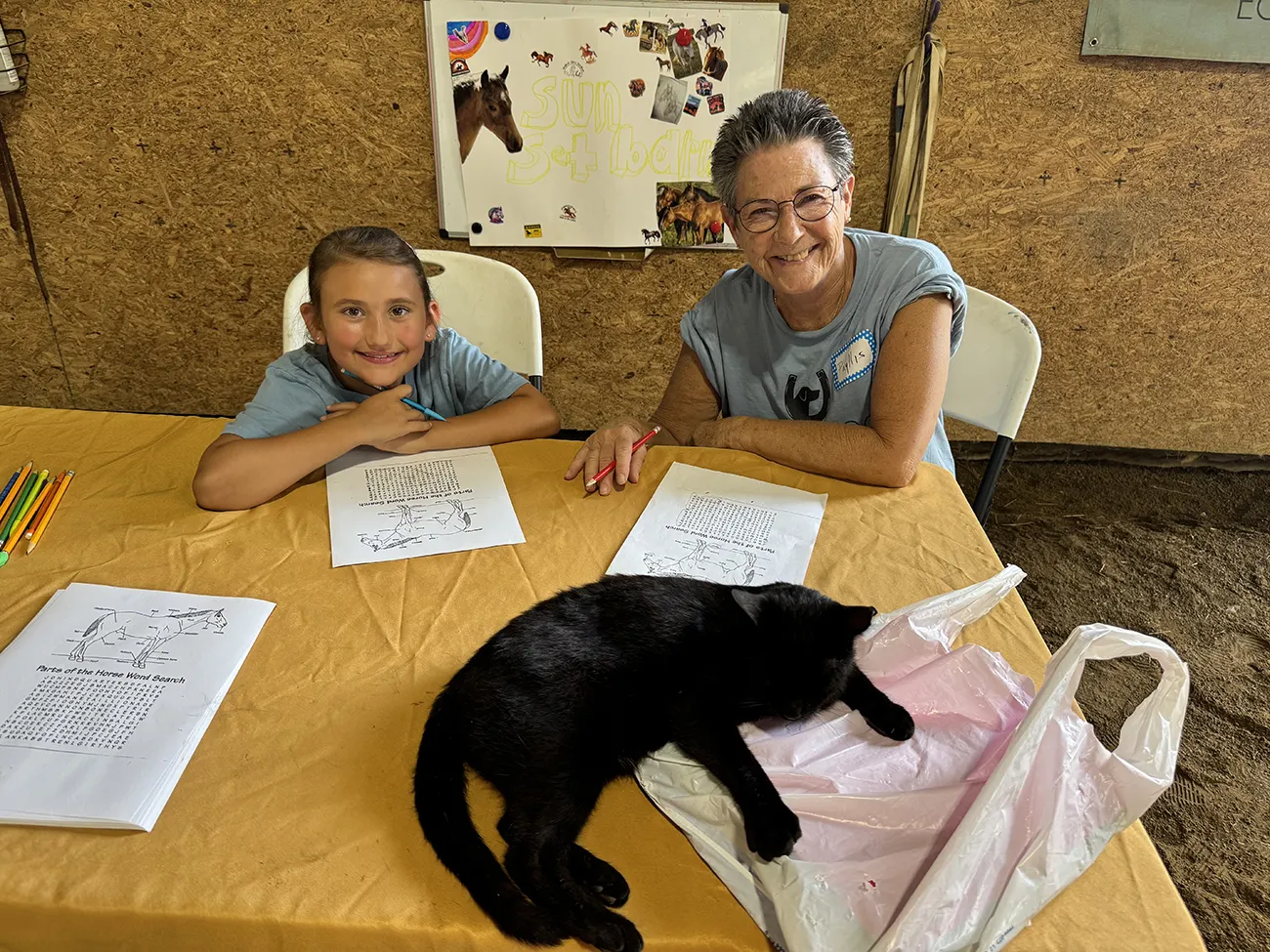

Since grooming is Phyllis’s forte, I assigned her to a rotation that introduced the campers to various aspects of horse care. Every day, Phyllis guides campers ages 4 to 12 through the tasks around the barn that she has come to love.

She shows the kids how to brush Bear’s long mane from the bottom up, after applying detangler to ease out the knots. She demonstrates how to safely pick Gypsy’s hooves. She points out the body language of the horses being groomed, and she helps fearful campers become more comfortable around the horses.